Transgresiones y transformaciones: identidad, cuerpo y memoria en la narrativa de Adriana García Roel, Irma Sabina Sepúlveda y Sofía Segovia[1]

Michelle Monter Arauz

Tecnológico de Monterrey

Resumen

Este artículo tiene el objetivo de analizar la narrativa de tres autoras del noreste de México, a través de las categorías de identidad, cuerpo y memoria. Las personajas principales de las obras elegidas experimentan la violencia y la migración como dinámicas que las movilizan a transgredir y transformar el territorio que habitan. De esta forma, propongo configurar este artículo como un mapa de transgresiones y transformaciones de lo que Gloria Anzaldúa denominó la borderland, ese territorio no solo geográfico sino también afectivo y corporal en El hombre de barro de Adriana García Roel, el cuento “El Pleito” de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda y El murmullo de las abejas de Sofía Segovia.

Palabras clave: Espacio, identidad, cuerpo, memoria

Abstract

This article aims to analyze the narrative of three-woman writers from the northeast of Mexico, through the categories of identity, body, and memory. The women characters of the corpus experiment violence and migration as a dynamic that mobilizes them to transgress and transform the territory that they inhabit. Therefore, my proposition is to configure this article as a map of transgressions and transformations of what Gloria Anzaldúa referred as borderland, the territory not only in geographical terms, but in relation to affection and the body and how it operates in El hombre de barro by Adriana García Roel, the short story “El Pleito” by Irma Sabina Sepúlveda and El murmullo de las abejas by Sofía Segovia.

Keywords: Space, identity, body, memory

Si para Henri Lefebvre el mille feuille es una analogía de la estratificación del espacio por medio del tiempo, el análisis que propongo en este artículo podría ser ilustrado como rebanadas en las cuales se muestran las múltiples capas sedimentadas en El hombre de barro de Adriana García Roel, el cuento “El Pleito” de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda y El murmullo de las abejas de Sofía Segovia. La propuesta de este artículo se imbrica con la noción de estratificación, categoría de análisis establecida desde la geocrítica, en la que se sostiene que el tiempo y el espacio están sujetos a una lógica oscilatoria que no aspira a ser un conjunto coherente, además de que la relación entre la representación del tiempo y el espacio es indeterminada.[2] Esta es una teoría que sigue la premisa de Fredric Jameson, quien enuncia que “lo que venimos llamando [sic] espacio posmoderno (o multinacional) no es meramente una ideología cultural o una fantasía, sino una realidad genuinamente histórica (y socioeconómica), la tercera gran expansión original del capitalismo por el mundo”.[3] En palabras de Bertrand Westphal, esta forma de concebir el espacio marca la transición de una lectura del mundo guiada por los residuos de las grandes narrativas a una lectura errática que surge desde la posmodernidad.[4]

Más aún, la premisa de este artículo es que toda representación conlleva una reducción puesto que solo indica una posición unilateral, la del autor o la autora. En última instancia, estos afanes de homogeneizar el espacio producen la creación de un estereotipo; no obstante, para minimizar la estereotipación, la postura de la geocrítica se sustenta en el análisis de múltiples representaciones del espacio a través de un corpus variado. Respecto al espacio homogéneo, Lefebvre indica que “del mismo modo que la luz blanca, uniforme en apariencia, se analiza en el espectro, el espacio puede descomponerse analíticamente, pero este acto de conocimiento llega hasta develar los conflictos internos de lo que parece homogéneo y coherente”.[5]

Así, una herramienta analítica para el desmantelamiento de la supuesta homogeneidad del espacio se da a partir del concepto de transgresión. Westphal sostiene que la transgresión pertenece a sistemas homogéneos con límites estables y explícitos para cruzar; a su vez, en los sistemas heterogéneos la transgresión es un fenómeno que cambia de carácter, dado que es absorbido por el sistema modificando los límites y las rutas de escape.[6] Cuando la transgresión se vuelve común en un lugar determinado, esto implica que el espacio obtiene la cualidad de la transgresividad.[7] Sin embargo, el análisis que se propone no trata de identificar espacios homogéneos versus heterogéneos, sino más bien, poner en evidencia la esencia heterogénea del espacio que se encuentra sometido a fuerzas que tratan de homogeneizarlo.

Si bien el concepto de transgresión será la herramienta principal de análisis de este artículo, estará atravesado por las nociones de memoria e identidad. Un elemento que se agregará al análisis será la representación del cuerpo como una forma de expresar la transgresión en el espacio dado que es el elemento que le otorga al ambiente una consistencia espacio temporal que puede ser examinada en la representación literaria.[8] Al respecto, Iris Marion Young propone la categoría de lived body ―en seguimiento del marco de fenomenología existencialista de Simone de Beauvoir que también retoma Toril Moi― para enfatizar la cualidad material del cuerpo femenino:

El cuerpo vivido es la idea unificada de la actuación y experimentación del cuerpo físico en un contexto sociocultural en específico; es el cuerpo situado. Para la teoría existencialista, la situación denota la producción de facticidad y libertad. Una persona siempre enfrenta la realidad material de su cuerpo relacionada con un ambiente. La piel tiene un color particular, el rostro posee rasgos determinados, el cabello un color y textura; todo esto forma parte de sus propiedades estéticas. Su tipo de cuerpo vive en un contexto específico ―al estar en contacto con otras personas, anclado en la tierra por la gravedad, rodeado por edificios y calles con una historia, socializado en un lenguaje en particular, con comida y un hogar disponible o no―, como resultado de procesos culturales y sociales específicos que exigen requisitos específicos para que se acceda a ellos. Todas estas realidades materiales están relacionadas con la existencial corporal y su ambiente físico y social constituyen su facticidad.[9]

Al determinar las características del cuerpo vivido de los personajes de El murmullo de las abejas, El hombre de barro y la narrativa de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda, se arrojará luz hacia los niveles de transgresividad del espacio representado; además, ésta también podrá ser vista en personajes caracterizados no como habitantes del lugar, sino como migrantes, forasteros e indígenas, quienes, a pesar de ser originarios del espacio, al ser construidos desde una visión etnocéntrica, se marca su distinción respecto a los demás.

Por otro lado, Doreen Massey propone al espacio como una “esfera de posibilidad de la existencia de la multiplicidad” y por lo tanto es un producto de las relaciones y, como tal, en constante construcción, es un producto social que nunca estará cerrado.[10] Este espacio siempre abierto a la multiplicidad de experiencias permite que los seres otros configuren un espacio heterogéneo en el cual asientan una identidad muchas veces en resistencia a las fuerzas de homogeneización. En el caso de la representación de quienes se han visto obligados a irse de su espacio, en su construcción se agudizan los marcadores de su lugar de procedencia y las diferencias con aquél a donde se dirige. En este sentido, también se observará la construcción de personajes exotizados por la mirada etnocéntrica que los representa como meros objetos ornamentales que, sin embargo, logran movilizar la trama en tanto corresponden elementos ajenos en la representación de espacios supuestamente homogéneos.

Este énfasis en la transgresividad de los espacios en la narrativa tiene el objetivo de desplegar la estratigrafía para observar cómo se configuran las nociones de identidad, memoria y el cuerpo en la obra de Adriana Roel, Irma Sabina Sepúlveda y Sofía Segovia. Así, se podrá observar en qué medida cada uno de estos elementos reconstituye o descompone el espacio referencial. Un concepto clave para este tipo de análisis corresponde al propuesto por Gloria Anzaldúa, quien entiende a la borderland como un territorio geográfico que también comporta territorios afectivos, simbólicos y geoculturales en el que se cruzan varios paradigmas y, por lo tanto, permite una transformación y un desplazamiento. De acuerdo con lo planteado este artículo se aboca al análisis de los diferentes tipos de transgresiones de los territorios ―geográficos, íntimos y corporales―, además de estudiar no solo las transformaciones del paisaje terrenal sino también aquellas del paisaje interior de los personajes, todo esto en relación con la identidad y la memoria.

Identidades y cuerpo

En el cuento “El Pleito” de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda, la forma epistolar permite que el personaje principal llamado Nicolasa reflexione sobre su identidad como madre y esposa en un contexto en el que su esposo forma parte de la comunidad de migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos.[11] Si bien de este diálogo bifronterizo solo tenemos una parte, en la carta de Nicolasa se manifiesta su sentir al respecto de que su marido se encuentre trabajando el Weslaco, Texas, y que, además, le escriba poco:

Por más que te digo que me escribas, te haces el sonso y me mandas en el sobre nomás el puro cheque, sin decirme siquiera que estás bien, que no te has enfermado de tus toses o que no te ha agarrado la tristeza de tener lejos a quienes tanto te queremos. Yo sé que ha de ser duro para ti andar en la aventura, y tratan siempre de fregar al hombre serio que se sale de su tierra porque no tiene capital para hacerse una parcelita o algo parecido. [..] Tú no andas por allá de aventurero, bastante batallamos para que consiguieras los papeles de la pasada para poder hacer algo por los hijos que nos echamos a cuestas cuando Dios nos lo mandó, así que no te quedes apelmazado como acostumbras.[12]

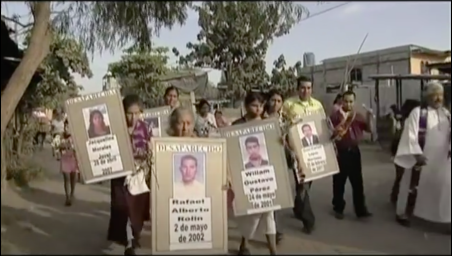

El devenir de la región que comprende el sur de Estados Unidos y el norte de México ha sido sumamente complejo y no es propósito de este trabajo realizar una cronología de tal proceso; sin embargo, es importante tenerlo presente dado que las creaciones de fronteras políticas afectaron tanto la construcción del espacio como las identidades de los habitantes de este territorio. En este sentido, es posible ubicar este cuento dentro del contexto de la diáspora mexicana. Dado que Nicolasa menciona que “bastante batallamos para conseguir los papeles de la pasada” es claro que la migración de Juan se realizó dentro del marco de la ley. A partir de este dato es posible inferir que “la pasada” se llevó a cabo dentro del período Programa Bracero, el cual fue un cambio significativo en las dinámicas migratorias y las regulaciones del trabajo forzado al que se enfrentaron millones de obreros mexicanos.[13] Weslaco, Texas fue destino de muchos trabajadores agrícolas que, como el personaje de Juan, se vieron obligados a dejar a sus familias para cruzar al otro lado para sobrevivir. Esta diáspora produjo nuevas experiencias en el espacio-tiempo, una de ellas representada en el cuento de Sepúlveda: la separación física, más no afectiva, de Nicolasa y Juan y la reconfiguración del espacio a partir de esta dislocación.

Al respecto, Briseño y Castillo brindan una perspectiva dicotómica de la diáspora al utilizar las categorías de masculino-femenino:

Puesto que diáspora significa dispersión, lo cual implica la dispersión de la semilla, se asume una cualidad seminal subyacente al fenómeno de translación. Lo que permanece en el hogar, por oposición, en la cultura (término etimológicamente emparentado con palabras como cultivar, habitar, proteger); es decir, la tierra feminizada.[14]

Siguiendo esta idea, la permanencia de Nicolasa en su hogar produce una suerte de feminización del espacio, una forma de habitar el mundo cifrado en su experiencia como mujer. Además, no es aventurado posicionar al territorio dislocado que se representa en el “El Pleito” como una borderland, categoría propuesta por Gloria Anzaldúa, que discute no solo los territorios geográficos sino también afectivos, simbólicos y geoculturales que comparten el mismo espacio. Anzaldúa indica que la borderland “está presente físicamente en donde sea que dos o más culturas se acercan una a otra, donde personas de diferentes razas ocupan el mismo territorio, donde se tocan las clases bajas, medias, altas, donde el espacio entre dos individuos se encoge con la intimidad”.[15] Esta propuesta se relaciona con las implicaciones de cruzar al otro lado porque se habla de un cambio de paradigma al mirar desde otras perspectivas, dado que solo de esta manera habrá una transformación y re-conocimiento.

Si bien en “El Pleito” es Juan quien realiza el acto físico de cruzar al otro lado, Nicolasa atraviesa por una transformación de su territorio y un re-conocimiento de su ser en el mundo. Para ilustrar lo anterior, se retoma que en la carta le confiesa a su marido las discusiones y peleas que ha entablado con la gente del pueblo, entre las que se encuentran Margarito, quien vende las muestras de medicinas que le llegan de forma gratuita: “Yo ya me pelié [sic] con él anteanoche y lo amenacé con avisarle a los del municipio de todos sus trafiques”; y Pajarito, el vendedor de quesos del pueblo, quien le indica que no le puede vender porque Tilana ya le apartó la mercancía. Nicolasa rompe la promesa que le había hecho a su esposo acerca de no pelearse con nadie en su ausencia y se dirige a casa de Tilana a cobrarle un dinero que le debía de hace meses, “Mira nomás, yo fajándome la tripa y esa desgraciada tragando queso. ¿Cómo tiene pa [sic] banquetearse y no pagar lo que debe?”.[16]

La construcción del personaje de Nicolasa es la de una mujer que transgrede del estereotipo de ama de casa abnegada. No es ocioso apuntar que esta transgresión es avante a su tiempo, sobre todo si se toma en cuenta que el cuento se publicó a mediados de 1960 y es una representación de la vida rural de principios del siglo XX. Para Nicolasa, el no quedarse callada y alzar la voz provoca que, tanto el pueblo como ella misma, se perciba como “peleonera”. Lo anterior puede contrastarse con la postura de Iris Marion Young, quien indica que las modalidades del comportamiento femenino, es decir, su movilidad por el espacio, tienen su origen no en la anatomía o el físico, sino en la condición de mujeres en una sociedad sexista.[17] La autora sostiene que las modalidades del comportamiento del cuerpo femenino, incluida su movilidad y espacialidad, existen en una constante tensión entre ser sujetos y ser meros objetos codificados por la mirada masculina.[18] En este sentido, la modalidad del cuerpo de Nicolasa se posiciona en el espacio al transgredir la norma cuando decide pelearse cuerpo a cuerpo con Tilana para tomar el dinero que le debe desde hace mucho tiempo. ¿Qué es lo que le permite a Nicolasa agenciarse su cuerpo y del espacio para reclamar lo suyo? Es posible que se deba a dos factores. En primer lugar, la ausencia de su marido elimina la mirada masculina que cosifica su cuerpo y regula su comportamiento incluso desde la distancia: “Ya sé que me vas a decir que no me entrometa en donde no me importa, y que mejor me quede callada[…] pero tú sabes que la gente nace respondona o apelmazada y a mí me tocó ser de las gallonas”.[19] En segundo lugar, que la lucha de la protagonista es con alguien igual a ella: Tilana también es una mujer que ha tomado control de su cuerpo y de su territorio dado que su esposo también ha migrado a Estados Unidos.

En el caso de El murmullo de las abejas de Sofía Segovia la principal testigo del devenir de la familia Morales es nana Reja, quien los acompañó desde que bajó de la sierra a finales del siglo XIX, hasta que regresa de la mano de Simonopio, a mediados del siglo XX. Durante estos años, Reja fue ama de crianza de cada uno de los niños que nacieron en la familia hasta que la vejez la imposibilitó para ese trabajo. Entonces, la nana escogió “pasar su tiempo eterno en el mismo lugar”, sentada en una mecedora a la intemperie en un cobertizo desde el cual podía dirigir su mirada hacia la sierra, hasta el punto en que “se había convertido en parte del paisaje y echado raíces en la tierra sobre la que se mecía. Su carne se había transformado en madera y su piel en una dura, oscura y surcada corteza”.[20]

Si la estratigrafía es el sedimento del tiempo en el espacio, el cuerpo de nana Reja se ha precipitado sobre la mecedora, como un árbol cuya corteza va formando múltiples capas a través de los años. Como es sabido, si se desea determinar la edad de un árbol se debe cortar una parte ―así como en el mille feulle de Henri Lefebvre― para revelar los anillos que muestran su crecimiento. El cuerpo de nana Reja funciona de una forma similar, los zurcos que estrían su piel representan las diversas capas temporales que ha experimentado a lo largo de su vida acompañando los devenires de la familia Morales. Ahora bien, la temporalidad es una cuestión que desarrolla Leonor Arfuch en función de la experiencia puesta en relato y su relación con la identidad anclada en un espacio:

[la temporalidad] es entonces el sostén por excelencia de la trama como mediación que da al tiempo -categoría en singular- su carnadura humana, diversa del tiempo cósmico o crónico, en tanto lo pone en relación con el acontecimiento y la experiencia. La identidad narrativa -personal, colectiva, se despliega así, a la manera de un relato interrumpido […] El espacio que tiene al cuerpo como referencia. El espacio estará entonces “habitado” en la relación entre pleno y vacío, emplazamiento y desplazamiento, un espacio vivido […] Así, la memoria será también inscripción, talla sobre el recuerdo -actualizado- de “haber vivido en tal casa de tal ciudad o el de haber viajado a tal parte del mundo.[21]

Las múltiples capas temporales que convergen en nana Reja despliegan una suerte de identidad abstracta en la que su cuerpo es la única evidencia de habitar el espacio. Si el lenguaje es una forma de expresar la experiencia, en el caso de la nana, a la ausencia del habla se impone otro tipo de evidencia del paso del tiempo: su cuerpo se configura como un palimpsesto que acumula surcos en su superficie. Los surcos representarían esas ausencias del habla, creando otro tipo de comunicación. Aunado a esto, se podría concluir que el personaje de nana Reja representa la memoria materializada en un cuerpo marchito, erosionado por el paso del tiempo.

De forma similar a la narrativa de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda, quien caracteriza a ciertos personajes desde una visión etnocéntrica ―el indio de “Martín Cuervo”, la adivina de “Camino de riel” ― nana Reja tiene una función casi ornamental, pero también en su construcción se advierten ciertos atisbos de una dignidad en constante resistencia:

Reja no consentía ser la curiosidad de nadie; prefería fingir que era de palo. Prefería que la ignoraran. Sentía que, a sus años, con las cosas que sus ojos habían visto, sus oídos escuchado, su boca hablado, su piel sentido y su corazón sufrido, había tenido suficiente para hastiar a cualquiera. No se explicaba por qué seguía viva ni qué esperaba para irse, si ya no le servía a nadie, si su cuerpo se le había secado, y por lo tanto prefería no ver ni ser vista, no oír, no hablar y sentir lo menos posible.[22]

En estos ejemplos se percibe una instrumentalización del cuerpo de Reja, la cual ha sido asimilada por ella misma. Dado que no hay motivo para su existencia dado que ya no le sirve a nadie decide “hacerse de palo”, fundirse con la naturaleza. El narrador omnisciente evita enunciar el origen de la nana, incluso, en el primer capítulo, “Niño azul, niño blanco”, se presenta a Reja como una mujer sin pasado, sin recuerdos sobre sus padres y sin la certeza de cuántos años lleva viviendo, es decir, sin una identidad. Por un lado, esta carencia separa a la nana Reja de su humanidad, pero al mismo tiempo la acerca a la naturaleza. Vale la pena recordar que, al ser nodriza, Reja brinda alimento y vida, y al no tener certeza de su pasado, su origen resulta inmemorial; de esta manera el personaje se vuelve una metáfora de la madre naturaleza. Aun así, el párrafo citado muestra, desde la perspectiva del narrador omnisciente, las características de ser independiente, incluso enuncia los rasgos de la personalidad de Reja como si el personaje se estuviera sometiendo a un arduo proceso de introspección en el que se reconoce como alguien que no tiene un motivo para continuar con vida si su cuerpo ya es incapaz de nutrir. La fina construcción de este personaje muestra una tensión entre ser una mujer cuyo cuerpo ha sido instrumentalizado por innumerables personas, y que, sin embargo, se aferra a su capacidad de reflexión sobre su propio ser en el mundo.

En otro tenor, lo que Reja recuerda de su vida pasada se ciñe a “la espalda [del hombre que abusó de ella] mientras se alejaba para dejarla en una choza de palos y lodo, abandonada a su suerte en un mundo que no conocía”.[23] Lo que Reja retiene de forma más nítida, casi en el plano detalle que propone Arfuch,[24] es su embarazo:

los movimientos fuertes en la barriga, las punzadas en los pechos y el líquido amarillento y dulzón que brotaba de ellos aun antes de que le naciera el único hijo que tendría. No sabía si recordaba la cara de ese niño, porque quizá su imaginación le gastaba algunas bromas al juntar los rasgos de todos los bebés, blancos o prietos que amamantó en la juventud.[25]

Según Hugo Bauzá, la etimología de la palabra recordar proviene de la voz latina cor-cordis que significa “corazón”, por lo tanto, el acto de recordar tiene una carga emotiva; “en el recuerdo se privilegia lo que, a veces de modo inconsciente, ha sido seleccionado no de manera racional sino afectiva”.[26] La selección de recuerdos de Reja, es decir, lo que no olvidó a pesar de la cantidad de años que vivió, corresponden a dos momentos que afectaron su experiencia como mujer: la violación y el embarazo. Incluso, cuando baja de la sierra hacia Linares, y el doctor la encuentra en la plaza muerta de frío, el narrador apunta que Reja “no supo cuándo la desvistió el doctor ni se detuvo a pensar que era ésa la primera vez que un hombre lo hacía sin echársele encima. Como muñeca de trapo se dejó tocar y revisar […] Luego se dejó vestir con ropas más gruesas y limpias sin siquiera preguntarse a quién pertenecían”.[27] La narración deja entrever que la vida de Reja hasta que llega a la casa de la familia Morales había sido una experiencia plagada de violencia y hasta cierto punto, la presentación del personaje como una mujer sin historia representa un acto de violencia en sí mismo, es extirpar la memoria y el origen para dejar solo una fantasma, una esencia de persona. Por eso el personaje de nana Reja resulta una especie de espectro que atraviesa la novela, sin emitir un solo diálogo, únicamente brindando su cuerpo a los demás.

De acuerdo con Young, el cuerpo situado en el espacio enfrenta una realidad material en relación con el ambiente en particular. En el caso de las mujeres, ellas aprenden a existir de acuerdo con la definición que la cultura patriarcal asigna, por lo tanto, se encuentran físicamente inhibidas, confinadas, y objetivadas.[28] Estas características pueden aplicarse al personaje de Reja, quien pasó la primera parte de su vida siendo usada por los hombres a su alrededor para que después la familia Morales también la utilizara como ama de crianza de su descendencia. Si bien la familia Morales trata a Reja como una persona, la narración deja muy en claro que la nana es propiedad de la familia, puesto que disponen de ella como herencia:

Cansado de vivir en el bullicio del centro de Linares, Guillermo había tomado la decisión extravagante de abandonar la casona familiar en la plaza para irse a vivir a la hacienda La Amistad, la cual se situaba a un kilómetro de la plaza principal y de la zona edificada del pueblo. Allí había envejecido Reja, y también él, cuya nana lo vio morir de un contagio. Y como antes, al heredar la hacienda a Francisco, el único hijo sobreviviente de una epidemia de disentería y de otra de fiebre amarilla, también le heredó a la vieja nana Reja, junto con su mecedora. [29]

Esta representación de una forma de experiencia de ser mujer en un espacio determinado puede ser contrastada con el opuesto de nana Reja: su patrona Beatriz Morales. Un episodio que ayuda a caracterizar al personaje de la matriarca se presenta en 1919, en medio de la Revolución Mexicana. En plena guerra, Beatriz se aboca a no dejar morir la tradición del baile anual del Sábado de Gloria en el casino de Linares, pero esto no se debe a una supuesta vacuidad del personaje sino a una profunda preocupación por el futuro que le dejará a sus hijas: “Quería salvar los recuerdos que Carmen y Consuelo tenían el derecho a crear, los vínculos que aún debían forjar viviendo su juventud en casa de sus ancestros”.[30] Beatriz desea que sus hijas construyan una memoria del pueblo de familiar, fundada en experiencias y relaciones que coadyuven a afianzar su identidad linarense. Este deseo no es espontáneo y si bien se encuentra motivado por la guerra interminable, también se imbrica con el devenir de una mujer como Beatriz:

Porque la vida le había prometido grandes cosas a Beatriz Cortés. Desde la cuna había comprendido que pertenecía a una familia privilegiada y apreciada que se sostenía con el fruto de su trabajo en sus tierras. […] Era un hecho que Beatriz Cortés conocería y haría amistad con la gente de valía de Linares y de la región. Que las hijas de las mejores familias serían sus compañeras de pupitre y luego de maternidad. Que por siempre serían sus comadres y que juntas envejecerían a la vista de todas para disfrutar una vejez llena de nietos. […] Temprano en la vida supo con qué tipo de hombre se casaría: de la localidad e hijo de familia de abolengo. Eso antes de estar en edad para ponerle nombre y cara a su elegido. Tendrían muchos hijos e hijas y la mayoría sobreviviría, eso seguro. Y al lado de su marido habría muchos éxitos y algunos fracasos, salvables, claro. También habría heladas, sequías e inundaciones, como las había en forma cíclica. Contaba con la certeza de que todas las promesas que le había hecho la vida se hacían o se harían realidad en relación con el trabajo y el esfuerzo invertidos. Sólo el potencial era gratis en la vida. El resultado final, el logro, la meta tenían un alto costo que ella estaba dispuesta a pagar, por lo que Beatriz Cortés nunca escatimaba esfuerzos para ser una buena hija, buena amiga, alumna, esposa, madre, dama caritativa y cristiana.[31]

Es notable que el narrador omnisciente presenta a Beatriz como “Cortés” y no con su apellido de casada, “Morales”, lo cual alude a una capa temporal anterior en el que se detalla su marco de pensamiento y sus ideales como mujer. Como se ha visto con Young y su propuesta del cuerpo situado, estos deseos se ven afectados por lo que la cultura patriarcal impone a las mujeres, sobre todo en un contexto de provincia a principios del siglo XX. No obstante, esto no implica que la representación de Beatriz sea la de una mujer frívola, sino de una persona que tiene claro su lugar en el mundo a partir de una estructura cerrada. Es lógico pensar que, al ser de una familia privilegiada, las oportunidades de Beatriz son mayores que las de una mujer como nana Reja. Sin embargo, a juzgar por el apartado anterior, Beatriz no dispone de la libertad, ni del deseo de salir del espacio cerrado que Linares representa para ella: toda su vida sucedería dentro de ese territorio limitado.[32] Incluso se podría argumentar que mientras más cerrado y controlado es el espacio de experiencia, la identidad que se refuerza despliega rasgos más homogéneos. Es decir, Beatriz Morales es un personaje con certezas fijas, las cuales han sido moldeadas por el tiempo que ha pasado en Linares sin que algo externo suceda. La lógica interna del pueblo afecta las convicciones del personaje, por esto resultan tan estáticas e inamovibles que logran configurar una identidad anclada en ese espacio limitado, al punto en que la única forma en que Beatriz concibe un futuro es a través de la herencia del pasado, de las tradiciones con las cuales la criaron a ella y posiblemente a todas las mujeres anteriores. De ahí que la obsesión por continuar con el baile anual sea la ruta para tratar de conservar algo para su descendencia: “¿Cómo puede enfrentar una generación a la siguiente, verla directo a los ojos y decirle: dejé morir una de las pocas cosas que di por sentado que te heredaría?”[33]

Estos afanes de conservación se hacen más evidentes una vez que la guerra irrumpe en el territorio volviéndolo liminal: una borderland en la que “cada acto de conocimiento significa tender un puente y cruzar, abandonar momentáneamente el territorio significado ―pre-visto― y transitar al terreno liminal y fronterizo donde solo es posible y productivo mirar, escuchar y transformarse en el contagio/contacto con lo imprevisto”.[34] Lo imprevisto ―la Revolución Mexicana― no le deja otra opción a Beatriz Morales más que transformar su sistema de pensamiento para no darle falsas esperanzas a sus hijas al respecto de un futuro que parece imposible: “No les haría promesas ni las ayudaría a construir en sus sueños al novio que tendrán, pues ni siquiera era seguro que éste llegara con vida al día en que tal vez se conocieran”.[35] El desencanto ante el futuro coincide con la idea general de que la guerra acabó con el tipo de modernidad exaltada por el Porfiriato en los albores del siglo XX en México, pero también por los ideales políticos de Francisco I. Madero que hicieron mella en una mujer como Beatriz:

En algún momento, antes de la guerra, con todas las promesas tangibles y ante sí, Beatriz se había sentido afortunada de ser una mujer de esa época y que sus hijas fueran mujeres del nuevo siglo. En esa era de maravillas las posibilidades se antojaban infinitas. […] Al principio había tenido la juventud y el idealismo suficiente como para comulgar con el principio de no reelección y el derecho al voto válido. De seguro, eso necesitaba el país para refrescarse y entrar de lleno en la modernidad del siglo XX. La sensatez reinaría, la guerra acabaría pronto con la deseada salida del eterno presidente Díaz y volvería la paz. [..] El autoengaño había terminado en enero de 1915, el día en que la lucha armada había llegado hasta su hogar y hasta su vida para quedarse como una invitada indeseable, invasiva, abrasiva, destructiva.[36]

Esta incursión narrativa en los pensamientos de Beatriz Morales hace evidente que en principio estuvo de acuerdo en la premisa de la Revolución Mexicana en tanto se prometía como otra ruta para “entrar de lleno en la modernidad”. No obstante, los eventos acaecidos en enero de 1915 terminaron por enterrar aquellos ideales de juventud: el asesinato de su padre por un batallón carrancista debido a una cena que ofreció al general Felipe Ángeles, culpable así de “fraternizar con el enemigo”.[37]

La muerte de su padre provocó en Beatriz una certeza: “La guerra la hacen los hombres. […] Esta que vivía no parecía la vida que se suponía debía tener Beatriz Cortés. A pesar de todo el sol salía y se ponía a diario, aunque a veces ese hecho la desconcertara. La vida continuaba. Las estaciones llegaban y se iban en un eterno ciclo que no se detendría por nada…”.[38] Las frases “la vida continuaba” y “eterno ciclo que no se detendría por nada”, aluden a la modernidad y del progreso, bajo el cual se ampara una idea de individualidad que, para el caso de Beatriz, son el escudo con el que se protege de lo que sucede afuera. Sin embargo, la transgresión a su espacio más íntimo resulta el asesinato a su padre que pone en crisis las ideas al respecto de la guerra. El caos ya no es más aquello que se ve en la lejanía, sino que irrumpe en su vida y trastoca su forma de ver el mundo. Esta transformación se presenta en las reflexiones de Beatriz al respecto de la situación global. De esta manera, a los eventos situados en la época de la Revolución Mexicana se les agrega otras capas, pero esta vez son sincrónicas: la Primera Guerra Mundial y la Revolución Rusa. En el discurso narrativo, los avances tecnológicos, como el ferrocarril, los barcos de vapor, el telégrafo, el alumbrado eléctrico y el teléfono ―la era de las maravillas, en palabras del personaje― de forma ineludible van acompañados de grandes despliegues de violencia:

Sin embargo, en lugar de aproximarse con tanta maravilla, las personas se empeñaban en alejarse: primero, en México, la Revolución. Luego, en el mundo entero, la gran guerra, que al fin parecía próxima a concluir. Más no conformes con estar sufriendo y peleando en casa, ahora los rusos hacían la suya en casa, hermano contra hermano, súbdito contra rey. […] Ella no sabía mucho de la historia de la realeza rusa ni del motivo de los conflictos con su gente, pero la había sacudido que, en pleno siglo XX, asesinaran a un rey junto con toda su progenie […] Entonces llegó a la conclusión de que Rusia y el resto del mundo estaban más cerca de casa de lo que parecía, pues en la región también circulaban historias de terror de familias entera desaparecidas, mujeres secuestradas y casa quemadas con su gente adentro. […] Al estallar la guerra Beatriz se había sentido segura en su pequeño mundo, en su vida sencilla, escudada tras la noción de que, si uno no molesta a nadie, nadie lo molestará a uno. Vista de ese modo, la guerra le parecía algo lejano. Digno de atención, pero lejano.[39]

Respecto a este apartado, me parece valioso recuperar de forma breve el pensamiento de Walter Benjamin, quien realizó una crítica a la historiografía que refería a los procesos históricos como acumulativos hacia una idea de progreso que terminó por expirar en el horizonte de la guerra. Lo anterior resulta notable en sus Tesis sobre filosofía de la historia, en especial en la tesis IX, en la que realiza la alegoría del ángel de la historia a partir del Angelus Novus de Paul Klee.[40] La crítica al historicismo es evidente al equiparar la idea del progreso con una figura de destrucción, empero, me interesa señalar que con esta alegoría Benjamin logra establecer la noción de la irrupción de un tiempo en otro. Entonces, el ángel de la historia es también una alegoría del punto en el que presente, pasado y futuro convergen en un instante, en un tiempo-ahora ―Jetztzeit, en palabras de Benjamin―. Para el caso de El murmullo de las abejas, la guerra es un evento que pone en sincronía a Linares con lugares tan alejados como Rusia; asimismo, termina con las esperanzas puestas en la modernidad como una dinámica que culmina en el progreso.

Bajo la representación del ángel de la historia, ese monstruo del progreso que se cierne sobre Linares, a través de la mirada de un personaje como Beatriz Morales permite observar, en términos de Leonor Arfuch, en plano detalle la vida cotidiana en medio de una guerra que ha hecho estragos en las diversas capas del espacio, desde la superficie hasta la intimidad, un territorio liminal en constante transformación. A partir de estas ruinas, la familia Morales apostará por transformar el paisaje de Linares.

Memoria íntima y colectiva

La primera línea narrativa de El murmullo de las abejas corresponde a la narración en primera persona del último descendiente de los Morales, quien, en aras de dar un último vistazo al espacio en que nació y creció, la casa familiar, viaja de Monterrey a Linares mientras le narra sus memorias al taxista. La segunda línea corresponde a la narración de esas memorias ancladas en el espacio, pero desde la perspectiva de un narrador omnisciente que se introduce en los personajes que componen el universo de la novela para contar la saga de la familia Morales y su impacto en la transformación del paisaje de Linares a través del cultivo de la naranja. Esta voluntad de transformación del territorio se enmarca en la Reforma Agraria, puesto que los Morales son terratenientes del lugar que ven como una amenaza la promulgación de la nueva ley. Una tarde, mientras se celebraba el compromiso de la hija mayor, Simonopio ―el niño de las abejas― llegó con un regalo para Francisco Morales: unas flores de azahar traídas desde Montemorelos, municipio contiguo a Linares, cuya característica principal es el cultivo de cítricos.[41] Después de observar las flores, Francisco se despide y sale hacia su despacho. Beatriz, contrariada por la grosería de su marido, decide ir tras él:

― ¿Qué haces, Francisco? ¡Tenemos visitas!

― Ya sé, pero no se van y yo tengo prisa.

― ¿Prisa de qué?

― De ganarle a la Reforma. […] El paisaje de nuestras tierras va a cambiar poco a poco, así me lleve diez años.[42]

Como es evidente, la postura de los Morales es tratar de defender la tierra que heredaron. Al encontrar un decreto de la Reforma que exceptuaba de expropiación las tierras plantadas con árboles frutales, el patriarca no dudó en cambiar el antiquísimo cultivo de caña por la naranja. Para su esposa, quien para ese punto de la trama ha sufrido los estragos de la guerra, la noticia del cambio de cultivo se une a los imprevistos que han ido transformando su territorio en liminal:

Beatriz tomó la noticia y la llevó directamente hasta la boca de su estómago, pero la compartió un poquito con la parte del corazón que se comprime con la tristeza: había vivido toda su vida rodeada de cañaverales porque su familia los cultivaba en sus tierras. Había crecido rodeada del verde de la caña, que parecía cubrir cuanta tierra se le concedía. Se había arrullado por las noches con el silbido que producía el viento al internarse y viajar entre la infinidad de varas y se había despertado, en las mañanas de ventisca, con el espectáculo de verlas agitarse como olas en un mar verde enfurecido, o como uno calmo cuando el viento no era lo suficientemente fuerte para agitarlas. ¿Qué sería en el futuro dormir sin su arrullo? ¿Qué sería asomarse por la ventana de su casa y ver el paisaje de sus recuerdos mutilado para siempre?[43]

Este pasaje se nutre de imágenes que evocan un espacio anclado en la memoria de Beatriz Morales. El paisaje de los cañaverales la ha acompañado desde su niñez y, a pesar de no ser un espacio cerrado, como una casa, sí corresponde a un espacio fundacional en el sentido que da Bachelard. Las imágenes que evoca Beatriz aluden a los espacios felices, es decir, los espacios que fueron amados. Para Bachelard, estos espacios primigenios “están en nosotros tanto como nosotros estamos en ellos […] somos el diafragma de las funciones de habitar esa casa y todas las demás casas no son más que variaciones de un tema fundamental. La palabra hábito es una palabra demasiado gastada para expresar ese enlace apasionado de nuestro cuerpo que no olvida la casa inolvidable”.[44] La pregunta final de Beatriz ― “¿Qué sería asomarse por la ventana de su casa y ver el paisaje de sus recuerdos mutilado para siempre?” ―, sugiere las capas temporales que atraviesan el espacio físico. Aún y que la transformación más radical del espacio provendrá del cambio de cultivo, es innegable que el territorio había atravesado cambios constantes desde el inicio de la Revolución al punto que ya ni siquiera era el que mismo que habitó en su juventud. El cañaveral de antaño, ese espacio fundacional, residía desde hace mucho únicamente en los recuerdos de Beatriz Morales.

Ahora bien, no todas las transformaciones del espacio corresponden con acciones voluntarias. Un ejemplo de otro tipo de transformación representada en las narrativas de Sofía Segovia y Adriana García Roel son las enfermedades. La epidemia es un elemento que cambia tanto la percepción del espacio como la formas de situarse en el territorio. Existe un tiempo sincrónico entre El murmullo de las abejas y El hombre de barro en tanto ambas presentan episodios cuya referencia se encuentra en el año de 1918, en los cuales una epidemia de influenza y viruela, respectivamente, modifica el espacio y las relaciones de sus habitantes.[45] En la novela de Sofia Segovia se muestra el proceso de remembranza a través del padre del protagonista quien camina por Linares después de la pandemia de influenza española que provocó la muerte de gran parte de los habitantes:

En el último vistazo que dio a la ciudad de sus ancestros, tras la llegada de la influenza, mi papá atestiguó de primera mano lo que trato de explicarte: te retiras de algún lugar, te despides de alguien y, acto seguido, esa existencia que dejaste atrás se paraliza por tu ausencia. En ese último recorrido que hizo por Linares se había quedado con la idea de que era el fin del mundo. Al menos el fin de su mundo. Todos los sonidos, los olores y las imágenes comunes se habían extinguido…[46]

Una especie de apocalipsis se genera por medio de la ausencia de elementos sensoriales, el mundo que conocía el padre del protagonista llegó a su fin: la pandemia, al aniquilar a los habitantes del pueblo hizo lo mismo con el “paisaje interior” que define Porteous como “la integración del mundo sensorial del olfato, sonido, gusto, y tacto, además del sentido de la vista”.[47]

En el caso de la novela El hombre de barro de Adriana García Roel, la enfermedad de la viruela se presenta como el acontecimiento que cambió para siempre el pueblo y sus habitantes, no solo en la capa del tiempo presente, sino que se incrustó en el espacio de sus recuerdos, conformando así un sitio lúgubre de la memoria del lugar. De entre todas las catástrofes que logró recolectar el narrador-protagonista durante su estancia, la viruela destaca porque las huellas de la pandemia son visibles ante la mirada del forastero. Es necesario indicar que el protagonista de la novela se configura como un observador letrado que siempre mantiene una actitud engreída y suspicaz en relación con los habitantes del ejido. Al principio de la narración, la voz narrativa menciona que: “Indiferente miré en un principio el vivir de los campesinos. […] Aquellos seres de color de tierra no me decían nada. Apenas y mi retina sabía de ellos. […] Un día accidentalmente, los sentí vivir. Así aletargado, así triste, así olvidado, así ignorante he encontrado yo al hombre de barro”.[48] Si en las narrativas de Segovia y Sepúlveda, la mirada etnocentrista se encontraba desde la construcción de los personajes-otros, García Roel creó un personaje que funciona como un prisma a través del cual se ve el espacio y los lugareños que conforman el ejido. Aunado a esto, la profesión del personaje, la medicina, se revela en el desarrollo de la trama, en tanto juzga los sistemas de conocimiento que los campesinos han construido por sí mismos.[49]

En un apartado, mientras el protagonista conversa con una familia del pueblo, nota “el rostro cacarizo de una de las muchachas”, y su mirada se posiciona en “las dos camas que había en el jacal mayor. Camas altas viejísimas, apolilladas. Me estremecí al imaginar la reciura de los días que en aquellos pobres muebles los enfermos habrían pasado”.[50] El cuerpo situado, en términos de Young, de los sobrevivientes posee las cicatrices de la peste y, así como los surcos en el cuerpo de nana Reja, aquellas fisuras en la piel representan las capas de un tiempo sostenido que, a fuerza del recuerdo, se cierne sobre el pueblo. De hecho, es por precaución que el protagonista no satisface antes su curiosidad acerca del episodio: “Siempre había querido averiguar más acerca de la epidemia de viruela, pero cada vez que me disponía a preguntar, el temor de despertar dolores aletargados estaba ahí para impedírmelo”.[51] Sin embargo, cuando se encuentra con Patricia, una habitante del pueblo quien asegura que ni ella ni su familia se enfermaron, tuvo la certeza de que solo ella podría recordar lo sucedido durante la epidemia sin el dolor de haber perdido a alguien:

[La epidemia] empezó allá pa’ onde viven Lourdes y Blas―me decía Patricia―, un día llegó un pobre hombre pidiendo posada porque se sentía enfermo. En uno de los jacales l’hicieron un campito y le dieron un rincón. Quesque el pobre venía de muy abajo, sólo Dios, porque él se jue poniendo más malo y más malo hasta que se murió. Y ni nunca llegaron sus gentes, a lo mejor no tenía parientes. Entonces cundió el mal: en el jacal onde le dieron ayuda al peregrino se enfermaron toitos y se murieron dos. Y asina más p’acá tantito y más p’alla. E donde quiera daba usté con el montón de enfermos [sic].[52]

Como en las narrativas de Segovia y Sepúlveda, un agente externo es el encargado de transgredir el territorio, “el pobre venía de muy abajo”, para irrumpir en la cotidianidad de los campesinos. Como la familia de Patricia y Manuel alcanzó a vacunarse, ellos fueron los encargados de ayudar a los enfermos y llevar a los muertos al panteón. Su experiencia se configura no desde el sitio de las víctimas, sino de los sobrevivientes, los testigos de las consecuencias de la enfermedad en el pueblo. Por lo cual no solo vieron morir a sus vecinos, sino que también tuvieron enterrar sus cuerpos sin vida. En palabras de Manuel: “Jueron días bien feos, no más afiguerese usté que casi no ‘bia jacal onde no estuvieran de luto. Ora, en ese tiempo llovía mucho y se ponía muy mal el camino… pos lloviendo y todo ai vamos hasta el camposanto, y como eran tantos los muertos cada qu’ibamos a sepultar uno hasta miedo nos daba pensar quien seguiría”.[53] Por un lado, se encuentra la descripción del trayecto a cementerio, el cual es dramatizado por los efectos climáticos como la lluvia, pero también se aclara que la carga de Manuel y Patricia ya no es el cuerpo vivido, sino un cuerpo pasivo, una carga que a juzgar por la narración, no será posible soltar por mucho tiempo. Además, como sugiere Micaela Cuesta, si la memoria “no dice la verdad de los acontecimientos, sino la parcialidad viva del recuerdo”,[54] la sustancia de esta narración no se encuentra en el recuerdo del pasado si no en las experiencias producidas en el acto de la remembranza. La tristeza de Manuel y Patricia es tal que el protagonista decide no continuar con “tan mortificante remoción de recuerdos”[55], pero ya es demasiado tarde, los estragos de la vivacidad de los recuerdos sobre la epidemia caen sobre él:

Por la noche el recuerdo de la epidemia me torturó […] Al día siguiente la impresión de la pesadilla me hizo ir al pueblo en busca de linfa. No la había. Sin detenerme a pensarlo tomé el tren y fui a dar hasta la ciudad. En el dispensario me encontré a un ex compañero de clases a la sazón estudiante de medicina. Me vacunó. Debe haber distado mucho de imaginar que el horror a las viruelas me había hecho recorrer un centenar de kilómetros. Y todavía ahora siento escalofríos en la espina cuando recuerdo aquella vez que por el viejo camino la viruela y la muerte se pasearon de la mano. [56]

En este apartado muestra la gran diferencia entre él y aquellos a los que observa: mientras uno puede ir y venir a placer, es decir, transgredir los límites del territorio, los otros, los campesinos, no disponen de esa virtud. Solo 100 kilómetros separan la pobreza del ejido del bienestar de la ciudad, y esta distancia parece diluirse en la búsqueda de una vacuna que parece reforzar el saber del médico y al mismo tiempo, protegerlo del contagio con lo imprevisto, tanto la enfermedad como la vida de los campesinos.

Consideraciones finales

Para finalizar, es importante recapitular que, a partir del ir y venir entre el pasado y el presente, las representaciones de la memoria cobran sentido con relación a la categoría de la estratigrafía. Como se ha demostrado en este artículo a través del uso del concepto de transgresión, los espacios representados en las narrativas de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda, Adriana García Roel y Sofía Segovia revelan la esencia heterogénea del espacio que se encuentra sometido a dinámicas que tratan de homogeneizarlo. Un ejemplo de este tipo de dinámicas corresponde con la presencia de personajes construidos desde un punto de vista etnocéntrico que operan como movilizadores de la trama porque son elementos ajenos que transgreden los límites de los espacios supuestamente homogéneos.

Además, la representación del cuerpo de las mujeres es una forma de expresar la transgresión en el espacio, como se vio con Nicolasa en el cuento de Irma Sabina Sepúlveda, además de la nana Reja y Beatriz Morales, en el caso de la obra de Sofía Segovia. Por otro lado, la gradación entre espacio privado y espacio íntimo permitió estudiar la transgresividad de los espacios domésticos, como la casa o incluso el hogar en términos más amplios como lo es en el caso del cañaveral de la infancia de la matriarca de El murmullo de las abejas. Aunado a eso, la transgresividad de los espacios es un factor que determina la liminalidad del territorio, por lo tanto, el término borderland operó como un puente entre las dinámicas de transgresión de los espacios y las transformaciones de territorios geográficos e íntimos, lo cual se vuelve evidente en el caso de las pandemias que asolan al pueblo de El hombre de barro de Adriana García Roel.

Bibliografía

Leonor Arfuch, “Cronotopías de la intimidad”, Espacios, afectos, pertenencias, Buenos Aires, Paidós, 2005.

Anzaldúa, Gloria, Borderlands/ La frontera: La nueva mestiza, trad. de Norma Elia Cantú, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/ Programa Universitario de Estudios de Género, 2015.

Bauzá, Hugo, Sortilegios de la memoria y el olvido, Buenos Aires, Akal, 2015.

Bachelard, Gaston, La poética del espacio, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1975.

Benjamin, Walter, Estética y política, Buenos Aires, Las Cuarenta, 2009.

Cuesta, Micaela, Experiencia de felicidad. Memoria, historia y política, Buenos Aires, Prometeo, 2016.

García Roel, Adriana, El hombre de barro, 2°ed. México, Ediciones Botas, 1956.

Lefebvre, Henri, La producción social del espacio, Madrid, Capitán Swing, 2013.

Massey, Doreen, “La filosofía y la política de la espacialidad”, en Leonor Arfuch (comp.) Espacios, afectos, pertenencias, Buenos Aires, Paidós, 2005, pp. 101-128.

Montemayor, Andrés, Historia de Monterrey, Asociación de Editores y Libreros de Monterrey, 1971.

Mora Ordoñez, Edith, “Cartas y viajes de ida y vuelta: diálogos bifronterizos en las novelas epistolares de Ana Castillo y Rosina Conde”, Literatura y Lingüística, núm. 38, 2018, pp. 103-125.

Segovia, Sofia, El murmullo de las abejas, Ciudad de México, Debolsillo, 2017.

Sepúlveda, Irma Sabina, Los cañones de Pancho Villa, Monterrey, Sistemas y servicios técnicos, 1969.

Szurmuk, Mónica y Robert Mckee Irwin (coords.) Diccionario de estudios culturales latinoamericanos, México, Siglo XXI Editores, Instituto Mora, 2009.

Valles Calatrava, José, Diccionario de teoría de la narrativa, Editorial Alhulia, Granada, 2002.

Westphal, Bertrand, Geocriticism: Real and Fictional Spaces, Nueva York/Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Young, Iris Marion, Female body experience: Throwing like a girl and other essays, Nueva York, Oxford University Press, 2005.

-

Este artículo está dedicado a Leonor Arfuch. ↑

-

Cf. Bertrand Westphal, Geocriticism: Real and fictional spaces, Palgrave/Macmillan, Nueva York, 2007, p. 37. Todas las traducciones al español presentadas en este artículo son de la autora. ↑

-

Westphal, Ibid., p. 75. ↑

-

Cfr., Loc. Cit. ↑

-

Henri Lefevbre, La producción social del espacio, Capitán Swing, 2013, p. 385. ↑

-

Cfr. Westphal, op. cit., pp. 44 y 52. ↑

-

“La transgresión corresponde con el cruce de límites que extiende el espacio marginal de libertad. Solo cuando se vuelve un principio permanente se puede hablar de transgresividad”. Westphal, op. cit., p. 47, la traducción es mía. En las narrativas a estudiar en este artículo, la transgresividad será evidente en tanto se arroje luz sobre las dinámicas que establecen constantes transgresiones en los territorios representados. ↑

-

Cfr. Westphal, op. cit., p. 65. ↑

-

Iris Marion Young, Female body experience: Throwing like a girl and other essays, Nueva York, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 16. ↑

-

Cfr. Doreen Massey, “La filosofía y la política de la espacialidad”, en Leonor Arfuch (comp.) Espacios, afectos, pertenencias, Buenos Aires, Paidós, p. 105. ↑

-

Para Edith Mora, la escritura epistolar se relaciona con la oportunidad de reflexionar sobre una misma para poder reconocer la subjetividad por medio de la escritura propia y el ejercicio de lectura con la figura receptiva de la correspondencia. Cfr. “Cartas y viajes de ida y vuelta: diálogos bifronterizos en las novelas epistolares de Ana Castillo y Rosina Conde”, Literatura y Lingüística, n. 38, 2018, p. 105. ↑

-

Irma Sabina Sepúlveda, Los cañones de Pancho Villa, Monterrey, Sistemas y servicios técnicos, 1969, p. 110. ↑

-

Cfr. Jorge Durand, “El programa bracero (1942-1964). Un balance crítico”, en Migración y Desarrollo, núm. 9, 2007, p. 28. [Dossier Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo]. “Los antecedentes inmediatos del Programa Bracero fueron el sistema de contratación conocido como el «enganche» y las deportaciones masivas de las décadas del veinte y treinta. Ambas modalidades de contratación y manejo de la mano de obra migrante fueron nefastas. El sistema de enganche, como negocio privado de las casas de contratación, fue un modelo de explotación extremo que dejaba en manos de particulares la contratación, el traslado, el salario, el control interno de los campamentos y las cargas de trabajo. Las consecuencias de este sistema fueron los contratos leoninos, el endeudamiento perpetuo, las condiciones miserables de vida y trabajo, el trabajo infantil, las policías privadas y las casas de contratación”. ↑

-

“Diáspora”, en Ximena Briseño y Debra A. Castillo, en Mónica Szurmuk y Robert Mckee Irwin (coords.) Diccionario de estudios culturales latinoamericanos, México, Siglo XXI Editores, Instituto Mora, 2009, p. 85. ↑

-

Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera. The New Mestiza, San Francisco, Aunt Lute Books, p. 19 apud Marisa Belausteguigoitia, “Prólogo” en Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/ La frontera: La nueva mestiza, trad. Norma Elia Cantú, México, UNAM-PUEG, 2015, p. 14. ↑

-

Sepúlveda, op. cit., p. 112. ↑

-

Cfr. Iris Marion Young, op. cit., p. 42. ↑

-

Iris Marion Young, Female body experience: Throwing like a girl and other essays, Nueva York, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 31-32. ↑

-

Sepúlveda, op. cit., p. 110. ↑

-

Sofía Segovia, op. cit., p.11. ↑

-

Arfuch, op. cit., p. 282. ↑

-

Segovia, op. cit., p. 11. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 12. ↑

-

Arfuch utiliza el término “plano detalle” para designar la descripción minuciosa de aquellos objetos que por cotidianos pasan inadvertido, lo cual que permite reflexionar sobre un espacio biográfico abierto a la esfera íntima. Leonor Arfuch, “Cronotopías de la intimidad”, Espacios, afectos, pertenencias, Buenos Aires, Paidós, 200, p. 250. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 13. ↑

-

Cfr. Hugo Bauzá, Sortilegios de la memoria y el olvido, Buenos Aires, Akal, 2015, p. 10. ↑

-

Sofía Segovia, El murmullo de las abejas, Ciudad de México, Debolsillo, 2017, p. 15. ↑

-

Cfr. Iris Marion Young, op. cit., p. 16. ↑

-

Segovia, op. cit., p. 19. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 55. ↑

-

Ídem. ↑

-

Para nana Reja también el espacio presenta una cualidad limítrofe, no obstante, hacia el final de la novela se da a entender que tanto Simonopio como ella se adentran en la sierra, de vuelta a la naturaleza que los concibió en principio. ↑

-

Segovia, op. cit., p. 55. ↑

-

Gloria Anzaldúa, op. cit., p. 14. ↑

-

Ibid., pp. 58-59. ↑

-

Ibid., pp. 59-61. ↑

-

Este episodio de la novela se relaciona con los hechos históricos sucedidos después de la Convención de Aguascalientes, en la que Francisco Villa rompe con Venustiano Carranza y designa como presidente provisional al Gral. Eulalio Gutiérrez. El General Felipe Ángeles, segundo al mando del ejército de Villa, entró a la ciudad de Monterrey el 15 de enero de 1915 y se autonombró Gobernador y Comandante Militar de Nuevo León. En marzo, tanto Ángeles como Villa salen de Monterrey para ir en busca de Carranza, y los carrancistas vuelven a tomar la ciudad. Cfr. Andrés Montemayor, Historia de Monterrey, Asociación de Editores y Libreros de Monterrey, 1971, pp. 318-323. Por estos sucesos se puede inferir que, en la novela, el batallón que asesinó al padre de Beatriz Morales por ofrecer una cena al General Felipe Ángeles formaba parte de las tropas carrancistas. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 64. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 60. ↑

-

“Es el ángel que ha vuelto el rostro hacia el pasado. Donde a nosotros se nos aparece una cadena de acontecimientos, él ve una única catástrofe que constantemente amontona ruinas sobre ruinas, arrojándolas a sus pies. Este ángel querría detenerse, despertar a los muertos y reunir lo destrozado. Pero desde el Paraíso sopla un huracán que, como se envuelve en sus alas, no le dejará plegarlas otra vez […] Esta tempestad arrastra el ángel irresistiblemente hacia el futuro, que le da la espalda, mientras el cúmulo de ruinas crece ante él de la tierra hasta el cielo. Este huracán es lo que nosotros llamamos progreso”. Walter Benjamin, Estética y política, Buenos Aires, Las Cuarenta, 2009, p. 146. ↑

-

En Montemorelos el cultivo de cítricos no es originario, sino que “El señor Joseph Robertson había plantado esos árboles a finales del siglo pasado, le contó entonces. Había llegado a construir las vías del ferrocarril y se había quedado ahí con sus ideas extranjeras. Un día se fue a California, para regresar con varios vagones llenos de naranjos que echarían raíz en Montemorelos, sin importarle que lo llamaran gringo loco y extravagante por no querer plantar caña de azúcar, maíz y trigo, como lo habían hecho ahí los hombres desde que se tenía memoria.” Segovia, op. cit., pp. 247-248. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 253 y 256. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 255. ↑

-

Gaston Bachelard, La poética del espacio, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1975, p. 30 y 45. ↑

-

Uno de los problemas del Nuevo León de 1918 fueron las epidemias. Según Montemayor, “Durante ese año hubo una de viruela, pero lo que realmente causó mucho desasosiego fue la de la llamada influenza española. Ésta apareció en Monterrey a principios de octubre y duró hasta mediado de noviembre de 1918. Alcanzó su intensidad máxima durante los días 20 y 21 de octubre, en que se registraron aproximadamente 100 muertes diarias en todo el Estado. El número total de las víctimas ascendió en Monterrey a 1,528 personas”. Andrés Montemayor, op. cit., p. 326. ↑

-

Segovia, op. cit., p. 168. ↑

-

Porteous, Landscapes of the mind, p. 196 apud Westphal, op. cit., p. 134 ↑

-

Adriana García Roel, El hombre de barro, México, Ediciones Botas, 1956, p. 10-11. ↑

-

Esto es más evidente en el episodio del tendajo de don Eugenio, quien es una mezcla entre boticario y doctor. La sorpresa de encontrar una figura de autoridad en medio del “mundo de jacales” provoca una imprudencia de parte del protagonista, quien cuestiona los métodos de don Eugenio. El letrado reflexiona al respecto de su actitud preguntándose “¿Qué facultad me asistía para acusar a don Eugenio? ¿Se había procurado que fueran siquiera acostumbrándose al empleo de algunas medicinas?”. Estas dudas respecto a la salud de los pobladores resultan un preludio para que el tema principal de su curiosidad surja en las siguientes páginas: la epidemia que azotó el ejido años atrás. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 105. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 99. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 101. ↑

-

Ibid., p. 105. ↑

-

Micaela Cuesta, Experiencia de felicidad. Memoria, historia y política, Buenos Aires, Prometeo, 2016, p. 127. ↑

-

García Roel, op. cit., p. 105. ↑

-

Ibid., pp. 105-106. ↑

Michelle Monter Arauz (Monterrey, 1993) es lingüista por la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, especialista en Literatura Mexicana del Siglo XX con Mención Académica y Maestra en Literatura Mexicana Contemporánea por la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Se ha desempeñado como traductora y editora, además de colaborar con crítica y ensayo en medios como Casa del Tiempo, Nexos y Este País. Su primer libro Narradoras del norte fue publicado por el Centro de Estudios Humanísticos de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.