A Rocío

La imagen de la orfandad

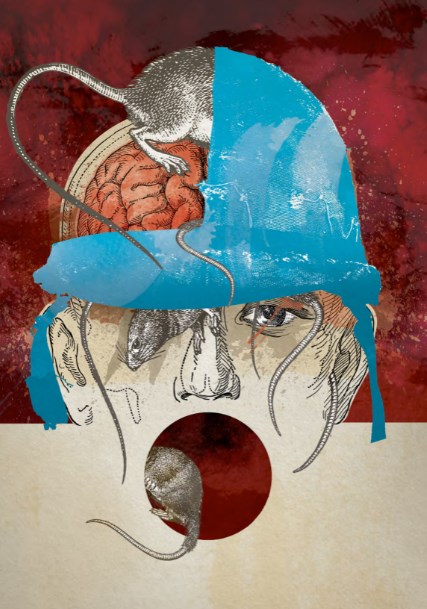

La orfandad es uno de los temas medulares de Pedro Páramo.[1] A partir de una prosa concebida desde la poesía, de una estructura narrativa combinatoria y de un estilo literario de gran poder suscitante, Juan Rulfo logró pulsar las cuerdas de la orfandad —y la búsqueda por redimirse de esa condición de falta originaria, no obstante que dicha búsqueda desemboca en una forma de abismamiento—. En el mundo de Pedro Páramo percibimos una orfandad que ni siquiera concluye en la ficticia región de los muertos; al contrario, desde esa región sombría podemos vislumbrar que la orfandad es irredimible y sin límites.

Hallamos el tema de la orfandad en uno de los poemas más antiguos de Occidente: La epopeya de Gilgamesh. El héroe mítico de Babilonia se siente desamparado cuando descubre que morirá de manera definitiva y, transido por la angustia, decide ir en busca del secreto que le otorgue la inmortalidad. Cruza el reino de la noche y llega a los confines del mundo pero, como no pertenece al orbe de los dioses, no tiene derecho a la inmortalidad y sólo le indican dónde hallar una hierba que hace recuperar la juventud; sin embargo, una vez obtenida, ésta le es robada por una serpiente. Con ese conocimiento y en esa pérdida, Gilgamesh asume su condición mortal, su plenitud humana, pero queda herido para siempre por un sentimiento de hondo desamparo. Y este sentimiento de orfandad lo hereda a toda la literatura occidental.

Sería fatigoso enumerar las obras que abordan los diversos tópicos de la orfandad que incluye el descenso a la región de la oscuridad —al mundo de los muertos, al hades, al sheol, al infierno, al mictlán o al inframundo— en busca de un conocimiento, de un padre, de un pacto o de algo mágico que logre absolver al personaje de su condición órfica, de su caída, de su falta, de su exilio, etcétera. De la Odisea a la Eneida, de la Divina comedia al Fausto y del Quijote a Pedro Páramo, sus autores nos muestran a héroes y antihéroes que descienden a las fronteras donde el hombre no tiene ya ningún asidero y busca asirse a algo que lo religue o lo devuelva a un posible estado de plenitud. Sin embargo, en el caso de Pedro Páramo, los personajes ni siquiera hallan asidero en la región de la muerte.

Cuando Juan Preciado va en busca de su padre, busca su origen, pero esa búsqueda es, en realidad y sin saberlo, un descenso a la región de los muertos, pues el edén originario evocado por su madre se ha convertido en un purgatorio donde las almas yerran sin sosiego, corroídas por sus culpas y remordimientos. El camino hacia el padre está sembrado de incertidumbre, miedo, muerte y, por si esto fuera poco, la orfandad alcanza su límite cuando Preciado se descubre alma en pena, un murmullo más en ese concierto de murmullos que lo han matado de miedo.[2]

Y aún más, como ha señalado Rodríguez Monegal, la novela empieza con la búsqueda del padre y termina con la muerte de ese padre a manos de uno de sus hijos.[3] Ahora bien, si consideramos la novela desde la cronología de sucesos, cuando Juan Preciado emprende la búsqueda del padre, éste ya ha sido asesinado muchos años atrás; y si de alguna manera Preciado es simbólicamente todos los hijos de Pedro Páramo, entonces concluiremos que el hijo decide buscar al padre después de haberlo matado; por eso no puede buscarlo sino en la región de los muertos y para ello es conducido por varios psicopompos: Abundio, Eduviges Dyada, Damiana Cisneros y, en la sepultura, por Dorotea. En este extremo, la orfandad es trágica porque, primero, es producto del abandono y, después, consecuencia del parricidio. La búsqueda del origen, el viaje iniciático en busca de la tierra de promisión, no podría desembocar sino en la muerte.

Dorotea dirige la orquesta de murmullos

En el fragmento 36,[4] cerca de la mitad de la novela, los lectores descubrimos que desde el principio Juan Preciado ha estado conversando con Dorotea y que los fragmentos sobre la infancia, adolescencia y ascenso del cacique Pedro Páramo son “murmullos” de otros tiempos que, a modo de contrapunto, se han integrado al relato de Juan Preciado. Y se han intercalado en su narración porque el mismo Preciado, a petición de Dorotea, le ha contado qué dicen los muertos de las tumbas vecinas.

En ese punto, cuando Juan Preciado y Dorotea conversan, abrazados en la misma tumba, los lectores descubrimos que la novela completa está articulada por murmullos, que ese archipiélago textual es una polifonía de ultratumba, que la historia de Comala y sus habitantes es contada por las almas en pena y que, en última instancia y como un nigromante, Rulfo ha invocado a los muertos y sólo ha sido un escucha, un amanuense de ese concierto de voces dolientes.[5] Los diversos tiempos narrativos convergen de pronto en un presente perpetuo, pues el tiempo de los muertos es vertical y sin orillas.

Dorotea, una mujer perturbada de sus facultades mentales y con una pierna tullida —le apodan La Cuarraca—, es quizá el personaje más complejo, profundo y lúcido de la novela, pues se revela como la memoria y la conciencia de un pueblo. Y es ella la que da origen a Pedro Páramo, pues en el fragmento 36 interpela a Juan Preciado: “Mejor no hubieras salido de tu tierra. ¿Qué viniste a hacer aquí?”, y esta pregunta nos remite al principio de la novela, a la apertura del texto y a la respuesta de Juan Preciado: “Vine a Comala porque me dijeron que acá vivía mi padre, un tal Pedro Páramo”.

En vida, Dorotea es una mujer marginada, es la loca del pueblo, no tiene familia, vive de la caridad pública y va siempre con un molote en el rebozo y lo trata como si fuera su bebé. Sin embargo, ya muerta se magnifica: dirige, a modo de directora de orquesta, la polifonía de voces. Además de dar pie a la narración, podemos decir incluso que es un personaje que inventa a su autor, pues inventa a Juan Rulfo para que éste escriba una historia cuyos hilos va tejiendo gracias a la mediación de Juan Preciado. Cuando Dorotea le pide a Preciado que le cuente qué dicen los muertos de las tumbas contiguas, está en realidad pidiéndole a Rulfo que escriba lo que dicen los muertos. En este sentido, Juan Preciado es una de las máscaras narrativas de Juan Rulfo. La novela Pedro Páramo es así una gran polifonía de ultratumba, y Rulfo es un nigromante que ha convocado a los muertos en ese espacio de la imaginación que llamamos creación literaria, un espacio donde Rulfo se diluye en el concierto de murmullos; es decir, el autor es devorado por su propia creación.

Demiurgo mediante la desaparición

El mundo de la novela es un mundo en ruinas, calcinado y de almas en pena, es decir, el apocalipsis ha sucedido, por eso es justo decir que el ambiente es post-apocalíptico. Cabe entonces preguntar: si todos están muertos,[6] si el narrador en tercera persona es incluso una voz fantasma en el coro de murmullos, ¿quién escribe la novela?

Sabemos, por supuesto, que Rulfo la ha escrito, pero hago esta pregunta retórica para señalar que el poeta-narrador Juan Rulfo no aparece en ninguna parte del texto que ha escrito.[7] A diferencia de los autores que son personajes, presencias, sombras o enunciados de autoridad en sus obras, el escriba de Pedro Páramo logró desaparecer de su novela, como actor y autor, y consiguió la proeza de crear un mundo regido por sus propias leyes. Mediante la escritura, Rulfo creó un mundo autosuficiente, un mundo que se reinventa a sí mismo a partir de la voz de sus personajes, un mundo que se impone a nuestra conciencia lectora como si nadie lo hubiese inventado, como si existiera más allá de un posible autor.

Y lo paradójico consiste en que Rulfo desapareció de su escritura porque logró elevar su orfandad a la condición de ley universal y, desde la poesía, nos impuso su desamparada visión del mundo.

Las dos vidas después de la muerte

Aunque el mundo narrativo de Rulfo parte de la cosmovisión cristiana y se comprende en ella, en los fragmentos 36 y 38, además de contener la clave de los hilos narrativos, hay un motivo que contradice a la escatología cristiana: aparte del alma, los restos mortales —la carroña, los huesos, el polvo— tienen conciencia del ser que han sido en vida y mantienen una forma de vida en la muerte —este tópico recuerda, por cierto, el soneto “Amor constante más allá de la muerte” de Francisco de Quevedo—. Ambos fragmentos, correspondientes a un mismo pasaje de la novela, han provocado equívocos diversos entre los críticos debido a su ambigüedad, pues la novela no explica cómo Juan Preciado abraza a Dorotea en la misma tumba, si ella y Donis, según lo dicho por la misma Dorotea, entierran a Juan Preciado. Citaré dos pasajes de cada uno de los fragmentos para exponer luego mis hipótesis:

[Fragmento 36, habla Dorotea:]

Y de remate, el pueblo se fue quedando solo; todos largaron camino para otros rumbos y con ellos se fue también la caridad de la que yo vivía. Me senté a esperar la muerte. Después que te encontramos a ti, se resolvieron mis huesos a quedarse quietos. “Nadie me hará caso”, pensé. Soy algo que no le estorba a nadie. Ya ves, ni siquiera le robé el espacio a la tierra. Me enterraron en tu misma sepultura y cupe muy bien en el hueco de tus brazos. Aquí en este rincón donde me tienes ahora. Sólo se me ocurre que debería ser yo la que te tuviera abrazado a ti.

[Fragmento 38, Juan Preciado y Dorotea conversan:]

—¿Y tu alma? ¿Dónde crees que haya ido?

—Debe andar vagando por la tierra como tantas otras; buscando vivos que recen por ella. Tal vez me odie por el mal trato que le di; pero eso ya no me preocupa. He descansado del vicio de sus remordimientos. Me amargaba hasta lo poco que comía, y me hacía insoportables las noches llenándomelas de pensamientos intranquilos con figuras de condenados y cosas de ésas. Cuando me senté a morir, ella me rogó que me levantara y que siguiera arrastrando la vida, como si esperara todavía algún milagro que me limpiara de culpas. Ni siquiera hice el intento: “Aquí se acaba el camino —le dije—. Ya no me quedan fuerzas para más”. Y abrí la boca para que se fuera. Y se fue. Sentí cuando cayó en mis manos el hilito de sangre con que estaba amarrada a mi corazón.

Pese a la ambigüedad y lo fragmentario de la novela, podemos conjeturar que Dorotea y Donis hallan muerto a Juan Preciado en la plaza de Comala y se disponen a enterrarlo; una vez que Preciado yace al fondo de la sepultura, Dorotea “decide” morir al pie de la tumba abierta; suponemos entonces que Donis la arroja sobre Juan Preciado y entierra a ambos. Esta conjetura explicaría las palabras de Dorotea citadas líneas arriba: “Me enterraron en tu misma sepultura y cupe muy bien en el hueco de tus brazos”.

En la tradición cristiana, el cuerpo es considerado cárcel del alma y en él radican las posibilidades de salvación o pérdida de aquélla. La religión es entonces una guía moral para salvarse, pues para el cristiano la vida verdadera no está en el más acá sino en el más allá y tiene que apegarse a los preceptos religiosos si quiere gozar de una supuesta vida eterna. Si la vida en la tierra es insoportable, el cuerpo debe prevalecer en los tormentos, pues su misión consiste en salvar esa “porción divina” del ser humano que se denomina “alma”. Sin embargo, en el caso de Dorotea, el alma y el cuerpo se enemistan y luchan; el cuerpo se rebela contra todos los preceptos cristianos y decide aniquilarse para dar fin a sus sufrimientos; es decir, opta por una forma de suicidio.

En esa lucha, el cuerpo vence porque la vida ha sido para él un dolor continuo, una carga inhumana; decide cuándo morir, cuándo renunciar a sí mismo para dar fin a sus padecimientos, y no le importa ya si esa renuncia significa, para el alma, la errancia sin sosiego y la pérdida de la salvación eterna. Camus escribe que “no hay más que un problema filosófico verdaderamente serio: el suicidio. Juzgar que la vida vale o no vale la pena de que se la viva es responder a la pregunta fundamental de la filosofía”.[8] Los personajes de Pedro Páramo no filosofan, viven y, en las orillas extremas de la vida, responden a la pregunta fundamental de la existencia. En este contexto, Dorotea descubre en un momento límite de miseria que la vida ha sido absurda y que es absurdo seguir “arrastrando la vida” en un mundo desolado y hostil, y decide que en esa frontera de lo insoportable “se acaba el camino”.

En esta perspectiva, si los huesos de Dorotea se resuelven “a quedarse quietos” a pesar de los ruegos del alma; si la lucha interior de Dorotea en sus últimos momentos, su agonía, es de una intensidad desoladora, pues decide abismarse para dar fin a su desesperación, esta lucha y esta renuncia a la vida es un sí a la creación literaria. Su suicidio engendra a un autor llamado Juan Rulfo. En vida habla poco (“parece ser que le sucedió una desgracia allá en sus tiempos; pero, como nunca habla, nadie sabe lo que le pasó”, dice Damiana Cisneros)[9] pero en la muerte, en esa condición de ser donde ni siquiera es alma sino cuerpo en estado de descomposición, es una psicopompa: una guía de almas en el más allá,[10] pues conduce las voces de los muertos de tal modo que logra una de las polifonías narrativas más originales y abismales de la narrativa moderna.

La conciencia separada

La doctrina cristiana considera que, en el acto de morir, el alma se separa del cuerpo, y que en el alma prevalece la memoria y la conciencia —esto explica el tormento de las almas en el Infierno de Dante, por ejemplo—. A su vez, considera que en cuanto el alma abandona al cuerpo, éste es sólo materia, carne para los gusanos, polvo en el polvo. Sin embargo, en la novela de Rulfo, la memoria y la conciencia permanecen en los restos del cuerpo inerte, en la cruda materialidad de lo que fue una persona; y los huesos guardan tantos recuerdos, tantas emociones, tantas pasiones y culpas como el alma misma. Aquí la visión de Rulfo entronca con el poema de Quevedo.

En “Amor constante más allá de la muerte” el alma, que sólo obedece a la ley del amor, pierde el respeto a la “ley severa”, y afirma que los amantes, aunque mueran, seguirán unidos en la región de la muerte, pero no sólo como almas sino que sus restos físicos seguirán ardiendo de amor, pues “polvo serán, mas polvo enamorado”. En el soneto, pues, los enamorados están juntos en cuerpo y alma, se aman incluso cuando los cuerpos son ya sólo ceniza y polvo, desafían todos los preceptos de la doctrina cristiana porque consideran que el amor no sólo vence a la muerte sino que vence a la ley del dios.[11]

Del mismo modo pero de signo contrario, los personajes de Pedro Páramo, tanto las almas errantes como los muertos en sus tumbas, recuerdan su vida —incluso pareciera que algunos de ellos no saben que están muertos y hablan como si estuviesen vivos—. En todo caso, como nos lo muestra Dorotea, cuando una persona muere, se divide radicalmente y se vuelve dos conciencias por completo ajenas entre sí, y cada una vive su muerte: el alma, en la pena sin fin; el cuerpo, en la rememoración plácida mientras se pulveriza su carne. En Quevedo, el alma se reúne con el cuerpo —aunque éste ya sea sólo polvo— con la única finalidad de eternizar la pasión amorosa; en Rulfo, el cuerpo se enemista y se divorcia del alma, y se condenan a un mutuo extravío.

El alma en pena ansía ser redimida: continúa sufriendo, se halla en condición de pérdida debido a los pecados cometidos por su cuerpo, de algún modo debe expiar sus faltas y, cuando encuentra a una persona viva, le pide que rece por ella, pues sólo mediante las oraciones de los vivos podría redimirse. (Este ruego de las almas en pena es lo que aterra a Juan Preciado cuando camina por las calles de Comala y estos “murmullos” son los que lo matan de miedo). Por lo contrario, los muertos en su tumba consideran su condición de materia inerte como algo mucho menos penoso que la vida, pues duermen buena parte del tiempo, incluso quizá sueñan en su muerte.

Para Dorotea, por ejemplo, estar en la tumba significa estar en el paraíso, pues ha dado fin a sus humillaciones, a su sufrimiento y a su miseria: “cuando a una le cierran una puerta y la que queda abierta es nomás la del Infierno, más vale no haber nacido… El Cielo para mí, Juan Preciado, está aquí donde estoy ahora”.[12] Dorotea considera que yacer en esa tumba —donde ya no padece ni carga con la responsabilidad de salvar su alma— es una de las formas de la redención. Dorotea significa “donada por dios”, ¿es recurso literario, paradoja o ironía que Rulfo haya escogido ese nombre para un personaje que, con discapacidad mental y física, subvierte de manera radical la visión del mundo cristiana?

Conclusión

Pedro Paramo se inscribe en una tradición que vertebra toda la literatura occidental. En la nekyia de Juan Preciado resuena, con la particularidad de cada caso, la poderosa nekyia de Gilgamesh, la de Odiseo, la de Eneas, la de Dante, la de Fausto, la de don Quijote. Una resonancia cuya música, cuya poesía, nos abandona en la orilla de una orfandad inapelable.

Bibliografía citada

.

Camus, Albert, El mito de Sísifo. El hombre rebelde, trad. de Luis Echávarri. Buenos Aires: Losada, 1957.

Lee Masters, Edgar, Antología de Spoon River, edición bilingüe, trad. de Jaime Priede. Madrid: Bartleby, 2012.

Moreno-Durán, R.H., “La sublimación y la expresión del mito”, en De la barbarie a la imaginación. La experiencia leída. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2002, pp. 367-375

Quevedo, Francisco de, “Amor constante más allá de la muerte”, en Obra poética, vol. I, edición de José Manuel Blecua. Madrid: Castalia, 1969, p. 657.

Rodríguez Monegal, Emir, “Relectura de Pedro Páramo”, en Narradores de esta América, t. II. Buenos Aires: Alfa Argentina, 1974, pp. 174-191.

Rulfo, Juan, Los murmullos [mecanuscrito: pre-texto de Pedro Páramo]. México: Centro Mexicano de Escritores, 1954, 127 pp. [Depositado en el Fondo Reservado de la Hemeroteca Nacional].

Rulfo, Juan, Pedro Páramo, edición de José Carlos González Boixo, 16a. ed. Madrid: Cátedra, 2002.

[1] Es también un tema cardinal en varios cuentos de El Llano en llamas y de la novela disfrazada de guion para cine titulada El gallo de oro; puedo afirmar incluso que la orfandad es quizá el tema primordial de la obra y la vida de Rulfo.

[2] Uno de los títulos previos de la novela fue Los murmullos, pues el autor llama, en el discurso de la novela, “murmullos” a las voces de los muertos.

[3] Emir Rodríguez Monegal, “Relectura de Pedro Páramo”, p. 186.

[4] El fragmento 36 empieza: “—¿Quieres hacerme creer que te mató el ahogo, Juan Preciado?” En este ensayo me baso en la 16ª. edición de Pedro Páramo preparada por José Carlos González Boixo (véase bibliografía) en la que establece de manera definitiva que la novela consta de 69 fragmentos. Recomiendo al lector esa notable edición crítica.

[5] Ya varios críticos han señalado las coincidencias entre Pedro Páramo y Spoon River Anthology de Edgar Lee Masters. Véanse, por ejemplo, los comentarios de R.H. Moreno-Durán en su ensayo “La sublimación y la expresión del mito”, pp. 367-375.

[6] Durante varias décadas hubo cierta controversia respecto de los personajes. Si nos basamos en la perspectiva del diálogo de ultratumba entre Dorotea y Preciado —que es el punto de vista que retomo en este ensayo—, todos los personajes están muertos. Si nos basamos en la lectura lineal de la novela, por supuesto que Juan Preciado llega vivo a Comala, asimismo están vivos los hermanos incestuosos y Dorotea; pero Preciado no sabe que Abundio, Eduviges Dyada, Damiana Cisneros y otros están muertos. Hago este deslinde sólo para evitar equívocos en este pasaje.

[7] Hay detalles que nos permiten establecer una relación entre la novela y la biografía de Rulfo; pero no me refiero a eso.

[8] Albert Camus, El mito de Sísifo, p. 13.

[9] Fragmento 37: “Al amanecer, gruesas gotas de lluvia…”

[10] Abundio, Eduviges Dyada y Damiana Cisneros son también psicopompos, pero sólo Dorotea alcanza el estatuto de guía polifónica al tomar como médium a Preciado-Rulfo.

[11] Quevedo, Obra poética, vol. I, p. 657.

[12] Fragmento 38: “Allá afuera debe estar…”

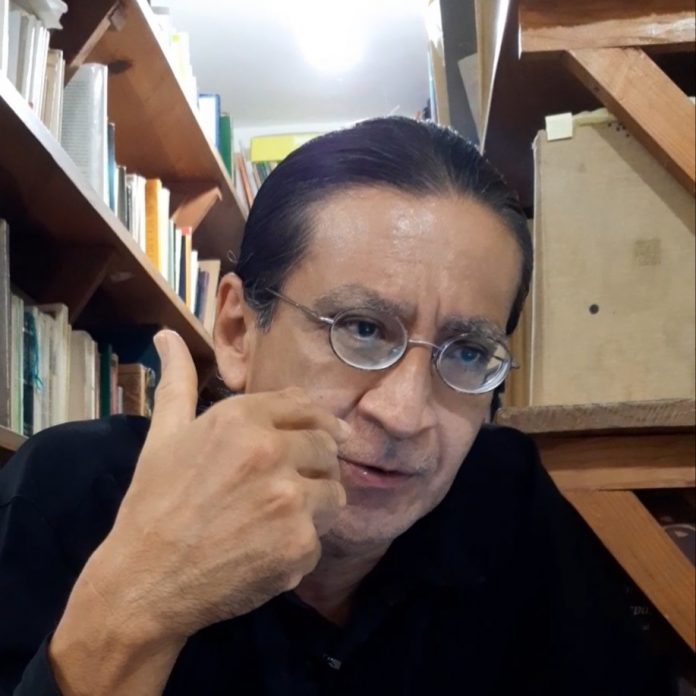

Felipe Vázquez ha publicado tres libros de poesía: Tokonoma (1997), Signo a-signo (2001) y El naufragio vertical (2017); cuatro de crítica literaria: Archipiélago de signos. Ensayos de literatura mexicana (1999), Juan José Arreola: la tragedia de lo imposible (2003), Rulfo y Arreola: desde los márgenes del texto (2010) y Cazadores de invisible (2013); y dos de varia invención: De apocrypha ratio (1997) y Vitrina del anticuario (1998). Obtuvo el Premio Nacional de Poesía CREA en 1987, el Premio Universitario de Poesía (unam) en 1988, el Premio Nacional de Poesía Miguel N. Lira en 1991, el Premio Nacional de Poesía Gilberto Owen en 1999 y el Premio Nacional de Ensayo Literario José Revueltas en 2002.

.